Did Marcel Duchamp steal Fountain from Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven?

- Bryleigh Pierce

- Aug 28, 2024

- 28 min read

Updated: Mar 23

In 1913, French artist Marcel Duchamp took a bicycle wheel, mounted it on a wooden stool and called it Art. Here, the male-dominated art history canon would have you believe, is where Conceptual art began, opening the door for a plethora of subsequent Modernist styles. Following this narrative, Duchamp continued quietly working on his ready-made sculptures until 1917 when he, now a founding member of The American Society of Independent Artists, decided to test his fellow board of directors’ commitment to an exhibition consisting of any and all artworks that are sent for display. In order to do so, he chose an ordinary urinal and signed it with a pseudonym, so as to no arouse suspicion of his involvement, before mailing it to the Grand Central Palace under the title Fountain. The resulting outrage and controversy surrounding the sculpture continues to this day for its radical redefinition of what constitutes ‘art’ and who can be considered an ‘artist’. But what is denied by so many scholars, writers, historians and academics, is that this narrative is missing a key detail – that Fountain is not a product of Duchamp’s experiment, nor was it his creation. In fact, an examination of the physical characteristics of the sculpture along with the historical circumstances surrounding its conceptualisation show that it can more accurately be attributed to the radical genius of Dada artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

At the beginning of his career, Duchamp’s preferred medium was oil paints on canvas, with his work heavily referencing the likes of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso as seen in Sonata (1911), Nude (Study), Sad Young Man on a Train (1911) and Nude Descending a Staircase No.2 (1912). After seeing little success in this medium, he quickly abandoned painting in 1913 when he started working on his sculptural ready-mades. Only able to exhibit two of his ready-made artworks, at the Bourgeois Gallery’s 1916 group exhibition titled Exhibition of Modern Art, Marcel’s work, again, went virtually unnoticed. On April 8, 1917, Duchamp had a breakthrough when he took an ordinary urinal from J. L. Mott Iron Works, signed the front-left side with a pseudonym and submitted it to The American Society of Independent Artists for exhibition at New York’s Grand Central Palace under the title Fountain. Some of the Society’s jury members contended “it was Immoral, vulgar”, and others stated, “it was plagiarism” and merely “a plain piece of plumbing”, as such, Fountain was rejected for the exhibition and promptly hidden behind a partition when the exhibition opened on April 11.1

On April 12, Duchamp found the urinal at Grand Central Palace and took it to Alfred Stieglitz’s studio to be photographed for the second issue of his Dada journal, The Blind Man, which he co-published alongside fellow artist Beatrice Wood and author Henri-Pierre Roché. Outraged that his sculpture was excluded from what The Society asserted as being an exhibition open to all who wanted to exhibit their art, Marcel immediately resigned from the committee he helped establish stating, “when we found [Fountain] we took it out and took it back...and then I gave my resignation to the committee, I didn’t even discuss or say why—I just gave my resignation and they accepted it gladly”.2

The following month, when the second, and final, issue of The Blind Man was released, Duchamp, again, denounced the Society stating, “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life... [and] created a new thought for that object. As for plumbing, that is absurd. The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges”. Several of his artist and writer friends also joined the reviling, such as Louise Norton who asserted The Society jurors were, “fairly rushed to remove the bit of sculpture... because the object was irrevocably associated in their atavistic minds with a certain natural function of a secretive sort”, adding that, “It was a sad surprise to learn of a Board of Censors sitting upon the ambiguous question, What is ART?”, and Alfred Stieglitz who argued that The Society’s “chief function is the desire to smash antiquated academic ideas”. Their first exhibition, he stated, “is a concrete move in that direction”.3 After arriving at Stieglitz's studio and being photographed, Fountain disappeared, leaving only traces of its existence in a single photograph and ambiguous mentions in a handful of letters, and, following the May issue of The Blind Man, Duchamp seldom mentioned Fountain and quietly continued with his ready-mades.

Over the next 15 years, Duchamp moved further away from art and increasingly began seeing himself as a professional chess player, travelling around the world and entering himself in tournaments with and against his teammates. By 1933, the era of highly trained German and Russian players dominating the chess circuit was well underway and after several years of being defeated by these significantly stronger players, Duchamp was forced to admit his inability to keep up with the changing world of professional chess and reluctantly switched to the slower-paced game of ‘correspondence chess’.4 After making this switch, he began to rebuild his artistic career by “repackaging his early work” although, by this time, the only one of his ready-mades to still exist was a comb from 1916 given to, and long forgotten by, Walter Arensberg. This problem, however, was easily solved in 1936 when he began making replicas of almost all his ‘lost’ artworks, all but for Fountain.5 It wasn’t until 1950 that Duchamp made a replica of Fountain, at the request of Sidney Carroll for the exhibition Challenge and Defy: Extreme Examples by XX Century Artists, French & American, which was to be held at the Janis Gallery from September 25 to October 21. After acquiring a similar urinal, Duchamp signed the same ‘R. Mutt’ pseudonym on the front-left side, although, unlike the replicas of his other works which were exact matches, Duchamp loudly claimed this version of Fountain and the story behind it, by also signing his full name on the back along with that of his alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, followed by the word ‘replica’. After being asked by Carroll why he hadn’t yet remade Fountain, Duchamp simply responded with, “Oh, no one asked me”.6 Three years later, Duchamp gave an interview to Harriet and Caroll Janis during which he discussed Fountain and his involvement in its creation, for the first time.7 Following his interview and exhibition at Janis’s gallery, Duchamp made two additional Fountain replicas, one in 1953 and another 1963, after which time he was again mute on the topic. That was until 1966 when Italian gallerist Arturo Schwarz made a deal with Duchamp to sell replicas of the sculpture, he then created a further eight, each of which were to be sold for $20,000 (equivalent to $196,000 in 2025).8

Fig 2: Fountain (1917, 1964 replica) | Fig 3: Fountain (1917, 1950 replica) |

It seems strange that Duchamp would spend almost 40 years neglecting to talk about an artwork that was having such a profound impact on the artistic community, especially when he was the person it was being credited to. In fact, Duchamp didn’t even allow his name to be associated with the artwork for over a decade until the late 1920s and only assumed its authorship in the 1950s when he began making his replicas. Stranger still that when he did, finally, begin discussing Fountain, he was unable to explain or recall key details such as why he chose a urinal, where the pseudonym ‘Richard Mutt’ came from and what influenced him in this artistic direction.

In his 1953 interview, the earliest account of Fountain and his association with it, Harriet Janis asked Marcel, “On the urinal—that was a scandal—wasn’t it?” to which he responded, not with an explanation of why he chose the urinal or the “scandal” the ensued, but with a confused ramble on where “Richard” came from, stating, “Richard Mutt—Richard was very—Richard I don’t know where Richard came from—maybe it was Richard Mott—I don’t think so because we wouldn’t want to—we bought it at Mott Works on Fifth Ave—and we called it Fountain—I don’t know why”. Sidney Janis then asked, “In relation to a specific example, I wonder if you would tell us something of your choice of the Fountain and how that came about?” to which he blabbered in response, “Well that was, I don’t know how it was, it was of course very—it had to be scandalous—the idea of scandal was—presided to the choice—to send something to the Independents—we were talking, Stella and I and Arensberg and I—we spoke of it for doing it and came to the idea of a urinal—then we thought we would buy one, you see of course it went with the idea of ready-mades—already existed then, you see it was at 67th St. here in my studio and all these ready-mades were on the ceiling—the idea of getting a urinal came all of itself, you see it was not difficult to have the idea and well, once the idea was there it was done—we would send it to the Independents and nom-de-plume because we didn’t want to attract the attention, not that we were ashamed of it at all, but it would have been silly on my part being one of the members of the Committee to do it as a form of reaction or as something of a revolutionary gesture and sort of play with my authority there to force it in, so to speak—I didn’t want to use it in connection with my position—so that’s why we introduced the word “Mutt” in it and I think of course it was a play on Mott works where we bought this thing and changed to mutt, m-u-t-t instead of m-o-t-t and Richard, I don’t know where Richard came—it must have been Richard Mott works”.9 Although, in that same interview, he also claimed that Mott was changed to Mutt “because of Mutt & Jeff”, a popular comedic comic strip, before later returning to his original claim in a 1966 interview with Otto Hahn, affirming that “Mutt comes from Mott Works, the name of a large sanitary equipment manufacturer... And I added Richard. That’s not a bad name for a pissotière. Get it?”10

Adding to Marcel’s own confusion regarding the events surrounding Fountain and his involvement, the few details he was able to give were incorrect – J. L. Mott Iron Works, where he claimed to have purchased the urinal, never sold that specific model nor did ‘Richard’ appear in the company’s name and no one named ‘Richard’ worked there. Furthermore, despite claiming that “we bought [the urinal] at Mott Works on Fifth Ave” cannot possibly be true given that the company moved its location from Fifth Avenue to New Jersey in July 1902, 15 years before he claimed to have made the purchase, and even his 1953 claim that the company “still exists” was false it had actually shut down in the early 1920s.11 His recollection of the events surrounding his resignation from The Society board of directors is also incorrect as, despite claiming he resigned after finding Fountain behind a partition on April 12 and determining that the committee had no intention of allowing anyone to submit their work, he stated in a letter to his sister that he had already resigned on April 11, the day the exhibition opened and before he found the hidden urinal.12 More recent suggestions that ‘Mutt’ was inspired by the German word for ‘poverty’ and the sculpture is an anti-war protest is highly improbable given that Duchamp didn’t speak German, nor had he ever visited the country, and it is therefore unlikely that he would have known the translation. Such confusion is easily cleared by a letter Duchamp sent to his sister two days after Fountain was rejected, a letter that was hidden until 1982 when, 15 years after Duchamp’s death, it was published by the Archives of American Art Journal. Stating that, “Une de mes amies sous un pseudonyme masculin, Richard Mutt, avait envoyé une pissotière en porcelaine comme sculpture [one of my friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture]”, Duchamp himself makes a record of the fact that Fountain was not his creation after all and his use of the feminine “amies” instead of the masculine ‘amis’, identifies this “friend” as a woman.13 Who was this female friend Duchamp credited with “send[ing] in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”? It was the eccentric, thieving and radical Dada artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

Despite being “dismissed by many as a pathetic madwoman” during her lifetime, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927) was nothing short of a revolutionary who pioneered the ready-made with her creations of what she called “junk sculptures”, along with her use of her own body in performance art pieces which she introduced into her work half-a-century before ‘the body’ and ‘artist as object’ became common themes in feminist artworks by the likes of Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke.14

Reflecting art history’s ‘man does art, woman is art’ axiom, the Baroness didn’t just do Dada, she was Dada – “she [was] the only one living anywhere who dressed Dada, loves Dada, lives Dada,” and, in 1922, she was identified by Jane Heap in The Little Review as being “the first American Dada” and the very embodiment of Dada itself.15 It could also be argued that she was one of the few New York Dadaists who truly believed in and exemplified the revolutionary spirit and dedication to destroying bourgeoise notions of meaning and order that bonded the first Dadaists in Zurich. The majority of male avant-garde artists, however, can be defined by their tendency to create radical art in their free time but continue to live traditional bourgeoise lives behind closed doors and hold staunch opinions about women’s continued role as domestic servants. These are the artists to whom the Baroness, and women like her, presented the biggest threat as they are ultimately driven by fear of the New Woman’s challenges to their perceived masculine superiority. Despite many chronicles of the early avant-garde art produced in the U.S. including vivid descriptions of her artistic practice, it is perhaps unsurprising that her total identification with every facet of the movement, especially her hatred of the bourgeoise and the fact that she was a woman in her thirties and single (shock horror!), is what led to her exclusion from its historical narrative.16 Much like the Surrealists’, whose objectification and belittlement of women in their circles would begin in the coming years, male Dada artists viewed themselves as the ultimate creator and expected women to be their muse, puppeted by their desires, instead of indulging in their sexual freedoms and enjoyment of antagonising bourgeoise society which the Baroness did so freely.

Woman, to Dada artists, is a mindless, bodiless, machine-like entity that is totally reliant upon man’s direction for materialisation and consummation. ‘She’ is a machine made by man as an incarnation of his own idealised image, ‘She’ submits to his every will but is incapacitated and aimless without his instruction – ‘She’ exists because of, and solely for, male desire. “That is why he loves her”, Dada writer and critic Paul Haviland declares in his statement of the woman-machine, because, “‘Her’ corporeality is only possible by the ‘He’ who is the creator”.17 Published in the November 1915 issue of the avant-garde journal, 291, Haviland’s description of the woman-machine was further explored by Francis Picabia and Marius de Zayas in the journal’s following issue wherein Picabia’s Violá Elle (1915) drawing was reproduced alongside his statement: “Here she is, an incomplete tubular machine: “she” is simply the HOLE of the target, whose reaction to the shot wad of fire from the gun initiates her own continual penetration”. Along with this, de Zayas’s visual poem, Femme!, (1915) was also included in the same issue which reads, “A Woman! comprising a man’s anxious desires. Her sassy arm proclaims its debt to its male author—I see ... how she loves to be a straight line traced by a mechanical hand.” She is, “harebrained”, and her dadaism is articulated through male desire: she “exists only in the exaggeration of her jouissances and in the consciousness of possession.... I see her only in pleasure”.18 The Baroness, whose phallic frolicking and feminisation of traditional masculinity was the most radical and total embodiment of Dada’s core beliefs, made no attempt to shrink herself into her male contemporaries’ idealisations of the ‘She’ who served them. Elsa existed for herself and for her art, she, therefore “had to disappear” from history, Amelia Jones notes. As, “even within Dada itself, such a blatant, parodic symbolisation of the continuing (if threatened) privilege of the male artist could not be allowed. It was imperative that the New Woman...be contained within the anxiety-reducing mechanomorphic forms of the machine image, not parading freely through the streets wielding a phallus clearly detached from its conventional role as guarantor of male privilege”.19

Duchamp’s inability to further contextualise Fountain was dismissed by the art world as being the result of almost 40 years between the Independent’s exhibition and when he began publicly allowing himself to be associated with the artwork. However, some scholars remained dubious of his involvement, including William Camfield, often considered one of the foremost authorities on Fountain and Duchamp’s artistic output, along with former chief curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, Kirk Varnedoe, and French art historian and critic Hector Obalk, all of who have written several studies that pointed to the conclusion that Duchamp could not have been responsible for Fountain. Their research culminated in 2002 with the publishing of Irene Gammel’s Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity - A Cultural Biography, wherein Duchamp’s letter to his sister, clearly stating “one of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”, first connected the Baroness to Fountain, successfully explaining how she developed the idea of Fountain after or while constructing her sculpture God (1917) and sent it to New York from Philadelphia via the residence of Louise Norton, with whom she was acquainted, closing the case on whether or not he was the creator with a definitive and undeniable “no”.20 Despite this, the transgressive feminism seen in Elsa’s brand of Dada is “still too advanced for many historians, who continue to portray her as mad or mentally ill”, likely because it is far easier for art history and its (male) writers to declare her insane than admit their history, and their male predecessors who wrote it, to be wrong.

This is exemplified in the work of writers such as Bradley Bailey who, in his 2019 article Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’: The Baroness Theory Debunked, discredits the use of Duchamp’s letter as conclusive evidence, referring to British historian Dawn Ades who had recently claimed that Gammel mistranslated the letter in her 2002 book which, Ades claims, actually translates to “One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”, instead of “sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”. Bailey thus concludes that this mistranslation has allowed others to use “Gammel’s findings to fashion a scenario in which the Baroness, inspired by the United States’s declaration of war on Germany on 6th April, sent a urinal from Philadelphia to the Independents exhibition in New York to proclaim her distaste for both America’s entrance into the war and the Independents alike”.21 Given that neither Ades nor Bailey speak French, or have any experience translating the language to English, it is understandable that they have not seen their own mistranslations, the first of which is seen in “aimes”, which translates only to ‘friends’, not ‘female friends’ as they assert, and the friend can be identified as being a female only due to the French language’s use of grammatical gender. Given that English is not a gendered language, when translated, this simply reads “one of my friends”.

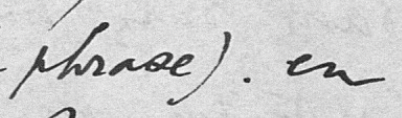

The second mistranslation made by Ades and repeated unchecked by Bailey is the inclusion of the phrase “who had adopted the pseudonym”, which has been translated from Duchamp’s “sous un pseudonyme masculin”. When translated into English correctly, this reads, “under a masculine pseudonym”, and nowhere in his letter does Duchamp use ‘qui avait adopté le pseudonyme masculin’ as would be required for Ades translation.

The third mistranslation, on which Ades’s and Bailey’s entire argument rests, is that of “avait envoyé une pissotière en porcelaine” being mistranslated to “sent me a porcelain urinal”, for, if it could be translated to “sent me”, Duchamp would have had to use the past tense possessive pronoun “m’a” which, in this context, would have been written as “avait m’a envoyé”. Therefore, given that Duchamp has not used any possessive pronoun, this phrase could not be correctly translated to “sent me” as Ades has attempted and can only be translated to “had sent a”. Additionally, in his letter, Duchamp made no indication that the urinal was sent to The Society on his behalf or as per his instruction, as such instruction would be read as ‘en mon nom’ (in my name), ‘sous mon autorité’ (under my authority), ‘j’ai elle donné l’autorité de’ (I gave her authority to), ‘comme je elle ai demandé’ (as I requested), ‘j’ai elle demandé’ (I asked her), etc. all of which cannot be found.

Furthermore, what Bailey fails to mention is that Duchamp’s letter was not translated by Gammel, as Ades had claimed, but by Dada historian and scholar Francis Naumann for his 1982 article Affectueusement, Marcel: Ten Letters from Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti, wherein several of Duchamp’s letters were translated from French to English by a team of five writers, historians and translators, including the French writer and translator, Patrice Lefrançois.22 Given that Lefrançois is both a professional translator and native French speaker, one would be hard pressed to successfully argue his translation to be incorrect in favour of Ades.

Questions of how Bailey could have made such an egregious error in his research, and how his basic fact-checking could show such negligence, are easily solved with a quick search of his other publications, which show his lengthy association with Naumann and include Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess (2009), which was co-authored by Francis Naumann, The Shock of the Nu (2013), a text published in the catalogue accompanying the 2013 exhibition Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase: An Homage shown at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, and Back to the Well: Fountain as Source (2017) also a text for an exhibition catalogue, published in Marcel Duchamp Fountain: An Homage, also shown at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art. If Duchamp’s letter had been mistranslated, as Bailey asserts, it is easy to see that he would be hesitant to hold his mentor, Naumann, liable for this error, given his status as a well-respected Dada historian and his importance to Bailey’s own career. In his 2022 article Dada Meets Dixieland: Marcel Duchamp Explains Fountain, Bailey asserts that, while “The need for greater clarity is not entirely without merit”, the “inconsistencies in Duchamp’s retellings of the narrative have made it difficult to construct a clear picture of the events that shape the history of Fountain”, and that inconsistencies in Duchamp’s memory have “been manipulated to contribute to the justification of an argument questioning Duchamp’s involvement in the creation of the work”. Barring the fact that Bailey has made his own inconsistencies and manipulations of history, ignoring that it was Naumann, not Gammel, who translated Duchamp’s letters, done with the explicit purpose of furthering his argument that the Baroness couldn’t have been responsible for Fountain, his indolence and failure to undertake any significant and independent research is exemplified in his statement that “This theory has recently been discredited”, for which he cites himself instead of any scholars who have peer-reviewed his article that supposedly debunked the theory, or who have made similar investigations into the topic.23

Through understanding the research of Naumann, Gammel, Spalding and Thompson, as well as recognition of Duchamp’s lack of interaction with the sculpture, one can undoubtedly conclude that Duchamp had far less to do with the creation of Fountain than he claimed later in his life. However, this alone is not enough to definitively attribute the artwork to anyone else, such an effort can only be made through a further examination of Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph of the original Fountain, after which, it becomes clear that the Baroness is the most likely artist responsible for its creation.

Stieglitz’s photograph gives two clues as to who the sculpture’s creator could be, the first is seen on the tag hanging from the urinal’s left installation bracket, on which, the address of the fictional Richard Mutt is given as “110 West 88th Street”. Some writers, Bailey included, have attempted to make the claim that, because this was the address of Louise Norton, who wrote the Buddha of the Bathroom text that accompanied Stieglitz’s photograph in The Blind Man, she is, therefore, the only other person possibly responsible for Fountain.24 In actual fact, while she did live at that address, in her husband Edgard Varese’s biography Norton noted that in April 1917 she occupied the first floor of the building, she was renting the second floor to Albert Gliezes and Juliette Roche, and the third floor was also occupied, possibly Norton’s mother who owned the building, although no name was given in the biography.25 While at least three people other than Norton were also in residence at 110 West 88th Street, this fact is often omitted by those attempting to insert her further into the narrative than she belongs, as Ades and Bailey both did in their respective articles. Also noted by Norton is that in April 1917 she employed a housekeeper, Mrs. Kiernan, who is believed to have been born in 1852. This is important to note as it opens the discussion to evidence that it was she who wrote “Fountain” and “110 West 88th Street” on the sculpture’s tag, as evidenced by the round script writing which was not taught in private or public schools beyond the 1890s when Louise would have been taught to write, but it would have been taught to Mrs. Kiernan. Such a hypothesis was made by Glyn Thompson in response to Bailey’s failed ‘debunking’ of his theory, stating that, “to Mrs. Kiernan, the housekeeper of Irish descent, what arrived without a label at 110 West 88th Street was, inarguably, a fualän – a urinal; but by the time it left the same address attached to a label completed in Mrs. Kiernan’s round hand it had become, inarguably, a fuarán – a fountain”.26

The second clue given in Stieglitz’s photograph is the most obvious – the “R. Mutt” signature. When comparing the handwriting of this signature with that of Duchamp it becomes inarguable that Duchamp most certainly did not write on this urinal, and when examining the Baroness’s handwriting, she can easily be identified as the writer. This can clearly be seen in a 2022 exhibition of the Baroness’s work at London’s Mimosa House gallery which featured an image of Fountain projected onto a door with a section of the Baroness’s Graveyard poem printed in her handwriting on the wall next to it.

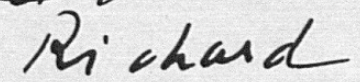

Most obvious to this analysis is that the Baroness uses all capital letters whereas Duchamp’s handwriting is cursive, although far less round than what is seen in Mrs. Kiernan’s handwriting on the label, but further inspection of several other key areas confirms that it is far more likely be her handwriting. In the letter Marcel sent to his sister, in which he confirmed that he did not send in the urinal, he wrote that it was sent using the “pseudonym, Richard Mutt”, and in doing so, gives us a clear example of his writing of the name which we can use for comparison – Duchamp used a capital “R” for “Richard” but a lowercase “m” for “mutt” and neither the “R” nor “m” match the lettering of the urinal’s signature, as the “R” is far more rounded on the right side and the leg curves before going back up and joining the next letter, and the “m” of Duchamp’s hand includes a hook leading into the top of the left side. Between these two letters we can also see that the spacing is far closer together than Duchamp usually allows. Additionally, the letter “U” in the signature is made with a single curved line and does not drop back down to the base or connect to the next letter, as is seen in Duchamp’s handwriting elsewhere, and, when using the letters “T”, Duchamp makes a slight curve before the right side drops down slightly. Finally, a significant difference can be seen in the angle of the writing. Where Duchamp writes on an angle with his rounded letters slightly tilting to the right, as was traditionally taught to students at the prestigious Lycée Pierre-Corneille secondary school he attended, the signature on the urinal is upright with very little tilt.

Fig 12: Duchamp's handwriting "U" in "Une" | Fig 13: Duchamp's handwriting "Mutt" |

Fig 14: Duchamp's handwriting "Richard" | Fig 15: Duchamp's spacing between full stops |

Comparatively, in the Baroness’s handwriting we can see stark similarities to R. Mutt’s signature, as well as direct matches. Not only did she use all capital letters when writing her poems, correspondences and her initials, she also used the same “R” that is seen on the urinal and, while she does tend to add a slight curve to the top of her “M”s, several of her poems feature the same angular “M” seen on the urinal with the spacing between the “R. M” being equivalent to the spacing she allows between her letters. Her letter “U” is constructed with the same single curved line and her letter “T” uses the same two straight lines that are seen on the urinal. Finally, the Baroness’s lettering stands upright and has the same sharp, angular shape.

Fig 16: The Baroness's handwriting "R" and "T" | Fig 17: The Baroness's handwriting "U" and "T" | Fig 18: The Baroness's spacing between full stops |

Fig 19: The Baroness's handwriting in her poem Teke Heart | Fig 20: The Baroness's signature |

We can also compare Duchamp’s signature he left on his other artworks, all of which he produced as replicas in his late life and all of which he signed with his name or his alias, Rrose Sélavy. On the back of Why Not Sneeze Rrose Selavy (1921) we can see Duchamp’s signature clearly written in the same cursive hand seen in his various signatures and letters, including the one sent to his sister on April 11. If, then, he was unconcerned with changing his writing for the signature of his feminine alter-ego, it would be strange of him to do so for the signature of Richard Mutt, an alias that, if indeed was Duchamp, he never used again.

With the vast amount of evidence certifying Duchamp could not have been responsible for Fountain, one would be naturally inclined to question why his false narrative is still perpetuated by scholars and taught to students. However, Ades’s and Bailey’s mistranslations and refusal to present any new, or even correct, scholarship on the topic points to a much larger issue in the work of contemporary historians and institutions and explains exactly why there is so much resistance to the Baroness. The historical canon that the likes of Ades and Bailey attempt to solidify will tell us that Duchamp was the first to use everyday and found objects for his sculptures beginning with Bicycle in 1913. But Pablo Picasso did this a year earlier with his use of discarded paper to construct Guitar (1912) and Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913), and Mary Delany (1700-88) was pioneering a similar process of making collages from paper she found and repurposed into floral arrangements in the early eighteenth century. Elsa, too, was making artworks similarly constructed out of found objects at the same time Marcel was beginning to, as seen in her Enduring Ornament (1913), a small metal band she found near a construction site which she determined was an artwork and added to her collection.

Unfortunate as it may be, her history of having men claim credit for her artworks is quite possibly the best rebuttal for the inevitable question of how such an act could go unnoticed – Morton Schamberg taking sole authorship of her 1917 sculpture God meant that she had no previous work that could attest to her making the similar Fountain, and society’s inability to understand her and her work as anything other than evidence of her “craziness” meant that she and her work was not taken seriously during her life.27 Not only did Schamberg assume credit for God, Duchamp himself later attempted to do so when he moved the sculpture from its original position and placed it among his other ready-mades while installing the Arensberg Collection display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1954.28 We can only guess what history would say had she asserted her authorship of God and had she not been considered ‘crazy’, but, even if this was the case, it is unlikely she would have played a larger role in history due to her return to Germany and shortened life, along with the censure of Germans in the lead-up to and during WW2, and, as we know, history usually records not who did something first or who initiated an idea, but who knew the people responsible for recording it or who had the most fame and notoriety. In the case of Fountain, there is also the added layer of the political and economic investment that has been made into Duchamp’s myth.

As Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson note, in addition to the countless artistic, curatorial and academic theories that have been based upon Duchamp’s false narrative, “national pride is at stake, for conceptual art was America’s contribution to Modernism, supposedly dating from 1917, not the 1960s when Duchamp’s work began to weave its spell”.29 Given that in the 1960s, when Duchamp began to take credit and proclaim the importance of Fountain, the Cold War was in full swing and the U.S. was looking for any reason to maintain the power they had found after establishing themselves as the centre for culture in the postwar world, it is difficult to imagine that this power would be relinquished back to Europe, as would be the case if the sculpture was attributed to the then newly immigrated, and exceedingly European in name and nature, Baroness Elsa, rather than the assimilated and Americanized Marcel Duchamp. Doing so would also mean correcting the narrative of Fountain being not an icon of anti-art or anti-aesthetic, as asserted by Marcel and those championing his myth, but an icon of artistic protest against a war being waged in Europe, thus admitting Europe’s affairs to be of prime importance to the West.

The notion of being rejected and cast aside only to persevere and prevail, also reflects fundamental elements of the idealised nature of the American people that was being projected to the world at this time, and such a tale is much more inspiring than the truth that Fountain was rejected because, as noted in a newspaper article just six days after the exhibition opened, the artist, “Mr Mutt”, who sent the urinal to The Society, “failed to complete the application process, and submit his $6 along with his urinal” and because it was delivered to the Grand Central Palace, “three weeks after the submission deadline”.30 This places even further doubt on Duchamp who was not only a founding member of The Society, and therefore highly unlikely to forget that all artworks would be accepted as long as the artist was a member and that they be received along with the $6 submission fee by the May 21 deadline, but who had ensured an artwork by his brother, Jacques Duchamp, had been properly submitted, complete with the submission fee and received before the deadline, which was thus included the exhibition.31

Added to this political motivation is the sheer amount of money that has been injected into the sculpture itself as well as the abundance of art and movements reflecting its anti-art and anti-aesthetic notions, including Conceptual Art, Abstraction and Abstract Expressionism, Fluxus, Pop Art and various others of the Avant-garde and Modernist movements. Since Duchamp made his Fountain replicas in the 1950s and 60s, their price tag has far exceeded the original $20,000 and, as the false narrative of their history and subsequent impact continues to be perpetuated, the cost continues to rise. In 1999 Greek art collector Dimitri Daskalopolos purchased the fifth of the eight 1964 replicas for $1,700,000 USD (equivalent to $3,209,591 USD in 2024) and, that same year, London’s Tate Modern Museum purchased a replica for $500,000 USD (equivalent to $943,997 USD in 2024). The avant-garde art that Fountain validated has also been highly sought after with Andy Warhol’s Liz (1963) portrait selling for $1,900,000 USD (equivalent to $3,587,190 USD in 2024) and Mark Rothko’s No.15 (1952) painting fetching $11,000,000 USD (equivalent to $20,767,947 USD in 2024), both at the same 1999 Sotheby’s auction where Daskalopolos purchased his Fountain.32 More recently, Duchamp’s replica of Belle Haleine – Eau de Voilette (1921) sold in 2009 for €8,913,000 (equivalent to €12,405,606 in 2024) and L.H.O.O.Q (1919, 1958 replica), what would be considered graffiti if it were from anyone else’s hand, sold in 2019 for €922,000 (equivalent to €1,117,490 in 2024).33 Even artworks that are a tribute to Fountain see high prices such as Sherrie Levaine’s Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp) which sold at auction in 2012 for $962,500 USD (equivalent to $1,318,609 USD in 2024).34 After purchasing his Fountain replica, Daskalopolos explained the hysteria the sculpture’s false narrative brings about, stating, “for me, it represents the origins of contemporary art”.35

Acknowledging that it was Elsa, not Marcel, who created the sculpture will not undo these sales, and it certainly will not diminish the importance of Fountain to the history and development of art. It would, however, recognise that the people who have written these narratives have often done so with extreme bias and it would encourage further exploration into history to uncover other injustices and false narratives leading to an understanding of how history can, and has been, manipulated for the benefit of patriarchal societies. Spalding and Thompson stressed that “the public has a right to believe what it reads on a museum label”, after all, it is within the hallowed museum that our tangible history has been collected, preserved and displayed for the public’s education and since its inception, we have been conditioned to believe the information we are given on labels to be true and given to us without bias. It is for this reason they declared that museums around the world with Fountain replicas in their collection, “should all re-label their copies of Fountain as “a replica, appropriated by Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), of an original by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927)”.”36 Although, with these and other museums who perpetuate such false narratives all snubbing the extensive research that has attempted to persuade them to admit their inaccuracies, it is difficult to remain optimistic and trusting of their label’s contents. Such naiveté is disallowed by the abundance of resources and research, no longer only accessible to the wealthy and connected.

1 Marcel Duchamp, "The Richard Mutt Case", in The Blind Man, no.2 (May 1917): 5.

2 Harriet Janis and Carroll Janis with Sidney Janis, Interview with Marcel Duchamp, conducted in 1953, unpublished, 2–14.

3 Duchamp, "The Richard Mutt Case".

Louise Norton, "Buddha of the Bathroom", in The Blind Man, no. 2 (May 1917): 5-6.

Alfred Stieglitz, "My Dear Blind Man", in The Blind Man, no.2 (May 1917): 15.

4 Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, "Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa's Urinal?" The Art Newspaper, November 1, 2014.

5 Spalding and Thompson, "Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa's Urinal?"

6 Carroll Janis and Louise Hidalgo, “Marcel Duchamp in New York,” November 22, 2016, in Witness History, produced by BBC Radio 4, MP3 audio, 12:04, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b083lt7z

7 Bradley Bailey, "Dada Meets Dixieland: Marcel Duchamp Explains Fountain", in October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 182 (2022): 61-96 https://doi.org/10.1162/octo_a_00470

8 Elena Filipovic, The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp, (United States: MIT Press, 2016).

9 Janis and Janis, Interview with Marcel Duchamp, conducted in 1953.

10 Otto Hahn, “Passport No. G255300”, trans. Andrew Rabeneck, in Art and Artists 1, no. 4 (July 1966): 10.

11 Bailey, "Dada Meets Dixieland".

12 Francis M. Naumann, "Affectueusement, Marcel: Ten Letters from Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti", in Archives of American Art Journal 22, no. 4 (1982): 2-19.

13 Spalding and Thompson, "Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa's Urinal?"

14 Eliza Jane Reilly, “Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven,” in Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 18 no. 1, (1997): 26-33, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1358677?origin=JSTOR-pdf

15 Jane Heap, "Dada," in Little Review (Spring 1922): 46, quoted in Amelia Jones, "'Women' In Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie," in Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, ed. Naomi Sawelson-Gorse (Boston: MIT Press, 1998), 142-173.

16 Rudolf E. Kuenzli, "Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and New York Dada," in Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, ed. Naomi Sawelson-Gorse (Boston: MIT Press, 1998), 442-477.

17 Paul B. Haviland, “We Are Living in the Age of the Machine / Nous Vivons Dans l’âge de La Machine,” in 291, no. 7/8 (September-October 1915): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.2307/25311795.

18 Marius De Zayas, “Femme!”, in 291, no. 9 (November 1915): 2. https://doi.org/10.2307/25311799.

19 Amelia Jones, “Women In Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie”, in Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, ed. Naomi Sawelson-Gorse (Boston: MIT Press, 1998), 142-173.

20 Irene Gammel, Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity - A Cultural Biography (United States: MIT Press, 2002), 222-30.

21 Bradley Bailey, "Duchamp’s ’Fountain’: The Baroness Theory Debunked”, in The Burlington Magazine 161, (October 2019): 804-810.

22 Naumann, "Affectueusement, Marcel”.

23 Bailey, "Dada Meets Dixieland”.

24 Bailey, ”Duchamp’s ’Fountain’”.

25 Glyn Thompson, "Sloppy Virtuosity at the Temple of Purity No. 36: Analysis of ‘Duchamp’s “Fountain”: the Baroness Theory Debunked’ (Bradley Bailey, Burlington Magazine, October 2019, 804-10)" in Burlington Magazine (December 2019): 1-21.

26 Glyn Thompson, “Sloppy Virtuosity at the Temple of Purity No. 36”.

27 Reilly, "Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven."

28 William A. Camfield, Marcel Duchamp: Fountain (Houston: Menil Collection, 1989), 59.

29 Spalding and Thompson, "Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa's Urinal?"

30 Anonymous review, "His Art Too Crude for Independents", The New York Herald, April 14, 1917, in Glyn Thompson, ”Duchamp’s Urinal – I – He Lied" in The Jackdaw (September/ October 2015): 10-20.

31 Thompson, ”Duchamp’s Urinal – I – He Lied".

32 Carol Vogel "More Records for Contemporary Art", The New York Times, 18 November, 1999.

33 Christie's, "Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) L.H.O.O.Q.", Christie's Auction House, 2019 (date of publication), https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6230284

34 Christie's, "Sherrie Levine (b. 1947) Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp)", Christie's Auction House, 2012 (date of publication), https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5559178

35 Vogel "More Records for Contemporary Art".

36 Spalding and Thompson, "Did Marcel Duchamp Steal Elsa's Urinal?"

Figure 1: Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917) photographed by Alfred Stieglitz.

Figure 2: Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917, 1964 replica). Glazed earthenware painted to resemble the original's porcelain, 36.0 × 48.0 × 61.0cm (unconfirmed). Tate Modern, London. Purchased in 1999.

Figure 3: Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917, 1950 replica). Glazed earthenware painted to resemble the original's porcelain, 30.5 × 38.1 × 45.7cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 125th Anniversary Acquisition. Gift (by exchange) of Mrs. Herbert Cameron Morris, 1998.

Figure 4: Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Self Portrait in her Greenwich Village apartment (December 1915). Image via Francis M. Naumann Fine Art. http://www.francisnaumann.com/ELSA/index.html

Figure 5: Theresa Bernstein The Baroness (1917). Oil on panel, 12 x 9in. Image via Francis M. Naumann Fine Art. http://www.francisnaumann.com/ELSA/Elsa03.html

Figure 6: Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven with Claude McRay (1920). Photograph negative 12.7 x 17.8 cm, Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection, https://lccn.loc.gov/2014714092

Figure 7: Marcel Duchamp, Letter to his sister Suzanne, 11 April 1917, Jean Crotti Papers, AAA-crotjean00005-112, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://edan.si.edu/slideshow/viewer/?damspath=/CollectionsOnline/crotjean/Box_0001/Folder_020

Figure 8: Duchamp, Letter to his sister Suzanne, 11 April 1917, (detail) Jean Crotti Papers.

Figure 9: Man Ray, Else Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (from The Little Review [September-December 1920]). © 1997 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society, New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Figure 10: Fountain (1917) photographed by Alfred Stieglitz (detail).

Figure 11: Installation view of The Baroness exhibition at Mimosa House gallery, London, 27 May - 17 September 2022. Courtesy the artist and Mimosa House, London. Photo: Rob Harris.

Figure 12: Duchamp, Letter to his sister Suzanne, 11 April 1917, (detail) Jean Crotti Papers.

Figure 13: ibid.

Figure 14: ibid.

Figure 15: Marcel Duchamp, Letter to his sister Suzanne, 17 October 1916, Jean Crotti Papers, AAA-crotjean00004-117, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://edan.si.edu/slideshow/viewer/?damspath=/CollectionsOnline/crotjean/Box_0001/Folder_020

Figure 16: Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Graveyard surrounding nunnery. Ms., Papers of The Little Review, University Archives, Golda Meir Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Figure 17: Freytag-Loringhoven, Graveyard surrounding nunnery.

Figure 18: ibid.

Figure 19: Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Teke Heart (Beating of Heart) (1921). Ms., Papers of The Little Review, University Archives, Golda Meir Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Photo: Charles Bernstein.

Figure 20: Ray, Else Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (detail).

Figure 21: Marcel Duchamp, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy (1921, 1964 replica). Wood, metal, marble, cuttlefish bone, thermometer and glass, 11.4 × 22.0 × 16.0cm (unconfirmed). Tate Modern, London. Purchased in 1999.

Figure 22: Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Enduring Ornament (1913). Iron, 11.5 x 8.9cm. Private Collection.

Figure 23: Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, God (1917). Wood miter box; cast iron plumbing trap. Height: 31.4cm, Base: 7.6 x 12.1 x 29.5cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950.